At times, the housing crisis is framed as an urban crisis in San Francisco or Los Angeles; however, workers are experiencing higher rents in smaller towns as well. Recently, Montanans have brought back the nickname "Boze-Angeles," for the city of Bozeman, Montana. It is a play on the nation's second largest city, Los Angeles's name, and due to Bozeman's influx of migration from California and its outrageous real estate market.

According to the National Association of Realtors' data, Montana is the state with the least affordable housing in the nation. Montana cities have seen rapid growth over the last 15 years, compared to the national average. For example, in 2023, the U.S. Census Bureau estimated the population of Bozeman is 57,305, an about 50 percent increase from 2010. This growth is necessary to support increases in tourism and related industries. From 2018 to 2023, the median home sales price in Bozeman went from $266,473 to $505,419.

Experts have different ideas about the appropriate responses to the housing crisis. Some argue for more rent regulations, which stabilize rents as a commodity on a "hot" real estate market. Still others have argued for mandatory inclusionary zoning laws that require that developers build below-market units. Below market often means that a set of units are financed to be available for a specific income bracket. Both efforts seek to support increased access to units, particularly for communities that are socio-economically depressed and experiencing other health disparities.

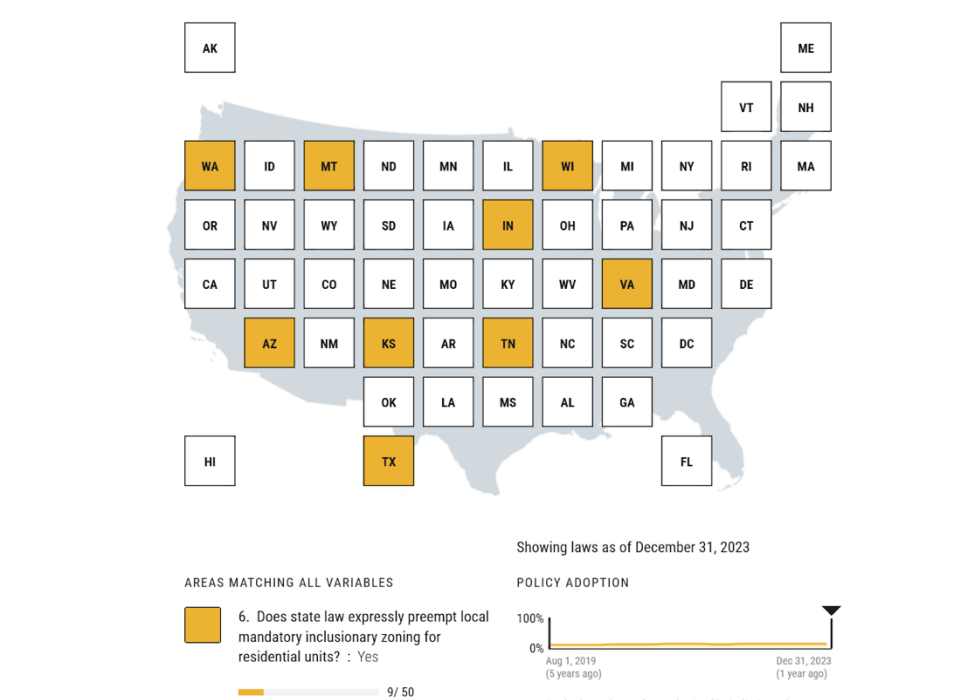

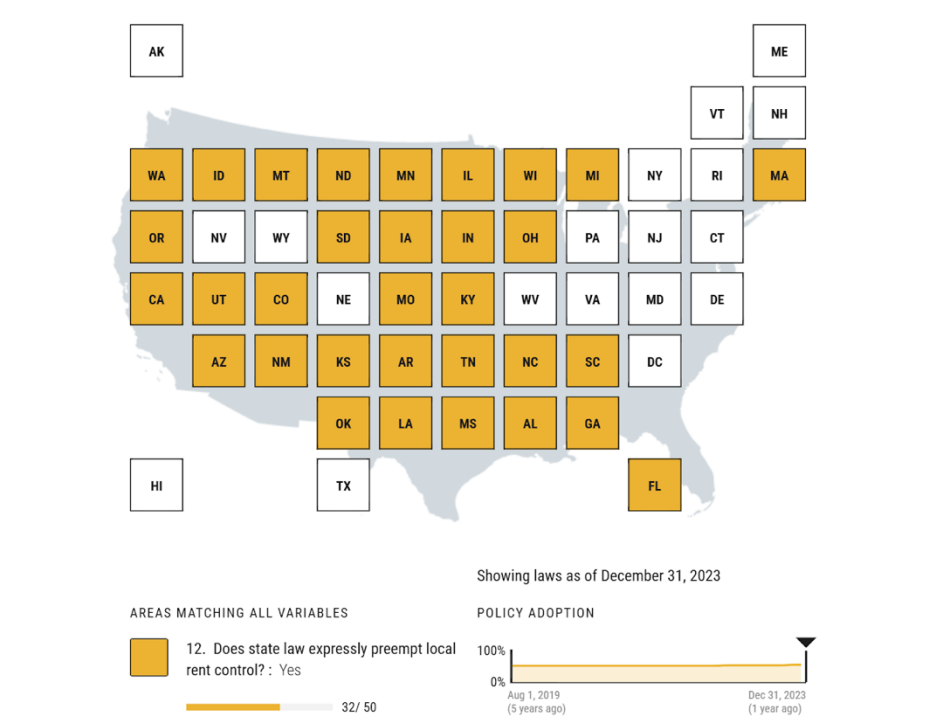

Instead of cooperation and collaboration, Montana has been acting to preempt local attempts at regulating the housing market, even though the city is desperate for new workers. In 2017, Bozeman passed a mandatory inclusionary zoning law; however, in 2021, Montana's legislature barred mandatory inclusionary zoning laws, including any requirement to make a payment in-lieu of constructing new below market units. And in 2023, Montana's Rent Control preemption law became effective, limiting rent regulation at the local level. The state has passed its own set of laws intended to spark housing development and the results are still unclear if their strategy will create more housing options.

For now, the fact remains that a growing tourism industry in the City of Bozeman calling for more temporary rentals like AirBnb or VRBO still lacks sufficient housing for its resident workers. Workers have to travel from 30 miles away to Three Forks to be able to find a house less than $400,000. Research has shown that long commutes (time in the care of more than about 30 minutes) contribute to poorer mental health, an increased risk of obesity, high blood pressure, diabetes, and some cancers, and a significant environmental impact that also trickles down to negative health effects, like increased risks for cardiovascular disease and respiratory issues. This is on top of the considerable stress and emotional toll of high rents and housing insecurity.

In "Boze-Angeles," we can start to transcend the urban-rural divide and start to understand housing as a larger systemic issue affecting all Americans. The rapid increase in population requires an experimental, curious, and evidence-based approach. They must be a mix of state and local solutions to drive housing production, while also ensuring that low- and middle-income people can afford to live near their workplaces.

There continues to be a need for a revolutionary approach to housing solutions as people continue to suffer in long travel distances to work. Some must live in their car or van and become homeless due to their overall inability to pay rent. Local controls can often have effects on all markets, but they ultimately are a call for more state and federal coordination. It's still not clear if the call is being heard or if even the call can be answered. In 2019, the Center for Public Health Law Research released a series of housing reports presenting frameworks, providing analyses and then presenting solutions around how legal levers can maintain existing housing, affirmatively further fair housing, enhance economic choice for the poor as well as increase the supply of new affordable housing. Six years later, solutions like a universal housing voucher or proactive housing code enforcement have not been adopted, not even in an experimental fashion.

Stories like Bozeman illustrate the real effect housing policy has on people’s lives and that it affects a wide swath of Americans. This is just one example of how states are stymieing local efforts to provide affordable housing in the community. According to LawAtlas data, eight other states have prohibitions on mandatory inclusionary zoning: AZ, IN, KS, TN, TX, VA, WA, and WI. Additionally, 31 other states preempt local rent control laws (AL, AZ, AR, CA, CO, FL, GA, ID, IL, IN, IA, KS, KY, LA, MA, MI, MN, MS, MO, NM, NC, ND, OK, OR, SC, SD, TN, UT, and WA). Generally, rent control preemption statutes are common. The only two states that have passed preemption laws since 2019 have been Indiana and Montana.

These policies are affecting a diverse swath of the United States and therefore, may require a diverse response. The Dept. of Housing and Urban Development will need solutions that must contend with the Bozeman housing market as well as the San Francisco and Los Angeles housing markets.

Still, workers cannot wait for Federal, State and local governments to become more aligned. For years, there has been a reliance on the Federal and State to build this housing. It may be time for the City and County governments to make their own below-market rate housing solutions.